In the previous chapter, human ‘sociality’ was identified as key to understanding human learning. Yet human beings are not the only species “living together in an organized way”. So, if sociality is foundational to how we humans learn, then the “living together” within human sociality needs the theorist’s close attention. Across this chapter It will be shown that research on tutoring has significantly contributed to our understanding of how learning is fundamentally rooted in social life. Which makes the topic of tutoring a very appropriate place to start when systematising acts of human learning. In short, it defines a sensible opening chapter for the present book.

Unfortunately, everyday use of the term ‘tutoring’ finds it applied to a very wide range of practices: extending from the management of a university tutorial to the authoring of books with such titles as ‘guitar tutor’. So, it is odd that the research paper most influential in establishing the importance of tutoring (Bloom, 1984) fails to define the term and so help narrow its reference. The following is suggested: ‘a more experienced individual intentionally promoting the learning of a less experienced individual within an episode of extended interaction between them’. Two assumptions are implicit: first, that the learner is a willing partner. And, second, that “an episode” may be extended into a series without violating the definition. However, if this definition is accepted, then notice also that ‘tutoring’ covers social engagements less well described by the educational language of ‘teachers/students’ or ‘experts/novices. For example, the definition above will fit the many situations in which a parent is giving guidance to a child during their shared play.

In this chapter, use of the umbrella term ‘tutoring’ will purposefully include such situations: that is, occasions where the term ‘guidance’ might be more typically used in everyday talk. There is a reason for this decision. A relatively broad meaning affords noticing important developmental continuities of process. Specifically, it alerts us to cultural continuities between those more informal or playful social exchanges of learning and the more structured ‘tutorial’ occasions of educational practice. However, one further constraint on what follows is important to acknowledge. The bulk of research to be cited here on tutoring is conducted within what anthropologists sometimes refer to as western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic (WEIRD) societies. Yet it is in those societies that the practice identified here as ‘tutoring’ thrives. Limitations on the universality of this practice – and hence the reach of the research reviewed here – is a concern re-visited towards the end of this chapter.

The influence achieved by that key research paper mentioned above (Bloom, 1984) arose from the compelling case it made for tutoring as a particularly potent act of learning. Bloom evaluated tutoring by describing research where its efficacy had been compared with other educational methods. He summarised results from studies by his own research students and he reviewed similar work that had been published elsewhere. Most research that he cited followed a conventional design: compare the test outcomes of students who had learned some topic through tutoring with the test outcomes of other students who had learned by some different, or ‘control’, method. Such comparisons involve evaluating whether the distribution of outcome scores from two such conditions overlap, or whether one set of scores is found to lie noticeably higher.

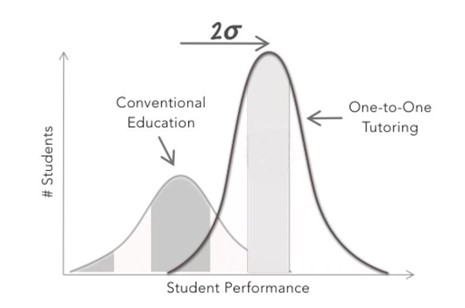

Differences between two distributions of contrasting test scores can be statistically evaluated in various ways. Bloom chose to express such differences in terms of standard deviations (a statistic derived from the shape or spread of a scores distribution and reported as the Greek letter sigma). Bloom’s memorable claim was that tutoring was a 2-sigma superior method when compared with classroom ‘business-as-usual’ control methods (see Figure 1). Briefly, the sigma statistic expresses where the average score derived from a target distribution (say for tutoring) would be positioned on the distribution of scores reported for the comparison/control distribution. Or in the more accessible terms used by Bloom to summarise his findings: “(a)bout 90% of the tutored students … attained the level of summative achievement reached by only the highest 20% of the students under conventional instructional conditions” (1984 p.4). This is a substantial difference.

.

Figure 1: Findings from Bloom’s review of tutoring versus conventional class teaching

The phrase ‘act of learning’ implies a focus on the agency of learners. Yet as with some other topics considered here, tutoring is surely an interaction – not a focussed experience pursued by learners acting independently. In short, it is a relationship: an interaction between one individual roughly cast as teacher/expert and one other (or small group) roughly cast as student/novice. In researching this relationship, it is possible to acknowledge such a social dynamic while still dwelling on what the individual learner brings to it. That is to say, how their expectations, emotions, dispositions and so forth determine its trajectory. That somewhat learner-facing strategy is the one adopted here. It should help position tutoring as one particular – but significant – act of learning available to learners: suggesting when and how that availability may be taken advantage of.

1) The conversational basis of tutoring

The definition of tutoring proposed above implies that it is a widespread human cultural practice and not one restricted to the form it often takes in classrooms. Nor are its participants always best described as “teachers” or “students”. For example, tutoring may be manifest in the workplace but also – and of special interest here – in the home. Moreover, its core definition, at least the one offered above, seems to allow that the pattern of communication within tutorial interactions is likely to vary – even while still maintaining a common purpose. So, forms of tutoring interactions may differ according to variation in the contexts and cultures within which they take place. The encultured nature of such interactions is a theme that will be taken up later in this chapter. Meanwhile, it remains possible to identify a pattern of interaction seemingly common to how we understand this act of learning.

Central to the aim of “intentionally promoting learning” within tutoring relationships is the management of a distinctive dialogue. Accordingly, research has focussed on the possible structures of, and outcomes for, this specialised way of talking. A paper by Mehan (1979) is helpful for orienting us towards just what it is that is ‘special’ about this. Mehan invites us to adopt a slightly eccentric stance. Namely, to overlook the familiarity of everyday dialogues and closely scrutinise them as rule-governed ways of talking. Problematising dialogue in this manner helps us notice an orderliness within it – and perhaps suggests mechanisms whereby that order can achieve certain learning consequences. Mehan asks us to reflect on two conversational exchanges, intentionally selected for their sparse content. First:

A: What time is it, Denise?

B: 2.30

A: Thank you, Denise

Contrast that with the following sequence, also involving two speakers:

A: What time is it, Denise?

B: 2.30

A: Very good, Denise

The first exchange might be overheard anywhere. However, in the second sequence, the third turn would be regarded as odd in many circumstances of everyday life – perhaps rather cheeky even. Yet it illustrates a format for conversational exchange that is quite commonplace in certain contexts: most obviously, classrooms. In a classroom there will be discrepancies of experience such that those with more knowledge (say, teachers) will be observed asking questions to which they themselves know the answers. In his article, Mehan goes on to elaborate the various ways in which this apparent violation of conversational norms is managed by teachers – a project elaborated further in classroom fieldwork reported by Edwards and Mercer (1989). That, in turn, had been built upon the work of Sinclair and Coulthard (1975) who documented what they termed the ‘IRF sequences’ of classroom dialogue: that is, ‘Initiation-Response-Feedback’.

The justification for close consideration of Denise-type simple sequences is as follows. First, there are a wide variety of choices available to Speaker A in exchanges of the second sort. There are both choices of A-style ‘initiating’ and choices of A-style ‘feedback’. It is worth exploring the fate of those different choices in relation to tutoring outcomes. Second, often these exchanges may not be quite so ‘simple’ as the one illustrated. In particular, they may extend over a longer period of turn-taking. Exchanges that are extended in that way are perhaps less characteristic of whole class conversation. They are more appropriate and practical within the intimacy of one-to-one tutoring formats. For instance, Edwards and Mercer (1989) did not regard IRF sequences addressed to whole classes as a species of ‘tutoring’ – as if such a practice might be applicable to large groups. Instead, they treated such exchanges as intending to establish or confirm “common knowledge”. That is, an evolving agreement about us (classroom members) all being on the same page and, therefore, possessing a readiness to construct new understandings that could evolve from that position.

Yet even if the IRF sequence is directed only at an individual class member, it seems unreasonable for such an isolated IRF sequence between a teacher and ‘Denise’ to qualify as a case of tutoring. While it may describe two people interacting in a learning context, it still appears too impoverished to fit the “intentional act of guidance” that is presumed in tutoring. This implies a need to consider the form taken by a more extended exchange that makes it a credible case of tutoring.

Graesser, Person and Magliano (1995) examined various occasions of tutoring and suggested a characteristic 5-part sequence as an elaboration of the more familiar 3-part IRF. The steps below are derived from their report (and further discussed by Chi (1996)).

- Tutor asks a question

- Student answers this question

- Tutor gives feedback on quality of that answer

- Tutor and student collaboratively improve that answer

- Tutor assesses student’s understanding of the answer achieved

The more traditional 3-part IRF exchange risks transmitting or confirming elements of knowledge in a mechanical or rote fashion. That may mean its impact on learners is more transitory. While implementing Steps 4 and 5 of the dialogue above promises a richer learning experience. Step 4 will often be particularly animated for participants. Indeed, examples of Step 4 often have whole 5-step sub-sequences embedded within them. The more advanced knowledge possessed by teachers may seem a guarantee that steps 4 and 5 will be straightforward to manage. But, through its repeated use, the knowledge of experts can become structured or sedimented in a manner sometimes termed “encapsulation” (Rikers, Schmidt and Boshuizen, 2000). This means it may prove troublesome to access, unpack, and communicate in tutoring contexts. Moreover, the demand of Step 5 assumes that learners have credible insight into their own understanding and, if they do, that they can communicate it usefully. Thereby, the execution of what seems a straightforward way of talking can be rendered quite a challenge.

Evidently, any tutorial dialogue will be shaped by ‘local’ circumstances: factors related to the chosen domain of learning, the level of a learner’s understanding within it, the time or tools available, and so on. Therefore, participants in these relationships will always need to tune what gets done so as to complement the particulars of their context. Sadly, interactions that can’t be scripted make awkward topics for research. Determining exactly what works is difficult when an improvised ‘tuning’ of action remains in the control of participants, and not the researchers. Yet surely we can make progress on outlining some general principles of effective dialogue – if not a tutoring template? This challenge will be addressed in the next Section, where one particularly influential model of tutoring will be introduced.

2) Dialogue as scaffold

Although these learning dialogues may inevitably be fluid or even idiosyncratic, this has not deterred researchers from examining what participants actually do within tutoring. Observers have attempted to systematise such talk – hoping that this may contribute to an understanding of successful learning outcomes. But what is a suitable period in learners’ lives for studies that could give a good return on the effort of observation? Bloom’s research (1984) was on university students – learners in the later stages of formal education. Yet, often, progress in understanding general matters of psychological functioning will arise from considering the very early years of human development. Processes of psychological functioning may be more clearly visible at times in development when complexities of individual or contextual differences are minimised. Also, the activities designed by researchers may then have simpler goals and participants may have a smaller (and so more manageable) set of means for achieving those goals. An early year’s research agenda thereby promises to deepen our understanding of learning processes.

Such considerations may apply to one program of tutoring research that was conducted in the mid-1970s and, since then, has been highly influential. Central to that program was a report by Wood, Bruner and Ross (1976) in which was described a study of 30 children aged 3, 4 and 5 years who participated in a tabletop building task. They had to combine 21 wooden blocks into a 9-inch pyramid while guided by an adult tutor. The tutor was required to provide support when children “stopped constructing or got into difficulty” (p. 92). Analyses of what the adult did in this situation suggested a metaphor for guidance they termed “scaffolding”. Subsequently, this term has achieved significant prominence in discussions of tutoring. Although it is not without critics: some have argued that the metaphor is easily pushed too hard (e.g., Stone, 1993). For example, it risks implying that tutorial support is fixed or static, in the manner of a construction site scaffold. Or, similarly, it is something to be withdrawn at the end of an activity rather than being a support that evolves and affords extensions. However, the metaphor remains a rich one, not least because Wood and colleagues went on to itemise its constituent moves. They describe six discrete interventions adopted by the adult in their study, each contributing to the children’s’ progress.

- Recruitment. Or the soliciting of a child’s “interest in, and adherence to, the task”

- Reducing degrees of freedom. Moves to reduce the constituent acts required for task completion

- Direction maintenance. Ensuring awareness of, and commitment to, the proposed goal

- Marking critical features. Highlighting task features that are particularly relevant to progress

- Frustration control. E.g., ‘face saving’ in relation to errors, or reassurances for slow progress

- Demonstration. Direct modelling. But, also, acting out an idealised resolution of the partially completed

This list of interventions might read clearly enough, yet it can be hard for a reader to animate them mentally if tied to that rather abstract block building task. An easier enactment may be possible by considering instead an adult giving tutorial guidance for solving a jigsaw – a type of puzzle often adopted for psychological research (McNaughton and Leyland, 1990). In that context, a more experienced adult might, for example, recruit interest by vigorously drawing attention to the reference picture, or reduce degrees of freedom by loosely grouping pieces by shape or colour, or mark the critical features of straight edge jigsaw pieces, and so on.

Exercising the intervention structure listed above may seem a matter of simple common sense: just obvious ways for a motivated tutoring partner to provide guidance. And yet research observations indicate that well-ordered conversational moves of that kind are far from common in tutoring (e.g., Bliss, Askew and Macrae, 1996; Cromley and Azevedo, 2005). In particular, less experienced tutors often resort to a version of ‘lecturing’, or they remain too detached, or they emphasise motivational more than cognitive support. So, in tutoring, the requirement on us to mobilise and fine tune these strategies may explain why we often find the responsibility for tutorial guidance to be quite a tiring experience. Moreover, the template for tutoring imposes still other demands – perhaps even more tiring – over and above executing such moves as those in the list above. Those are described by Wood and Middleton (1975) and Wood, Wood and Middleton (1978) who emphasised two further overarching approaches to a tutoring interaction that were particularly associated with task success: these they termed ‘contingency management’ and ‘fading’.

The first was expressed in terms of the “contingency shift principle”. This identifies two matched responsibilities: namely, the tutor increases their control of the task when the student is failing, and decreases control when the student is succeeding. (Some authors, such as Van de Pol, Volman and Beishuizen (2010), suggest that this form of ‘contingency management’ is sufficiently important that the term ‘scaffolding’ should only be applied to tutoring where it is clearly present in the interaction.) Wood and colleagues proposed that task outcomes depend less on the absolute amount of control exerted and more on how its applied: specifically, how far control is adapted to the learner’s momentary understanding. Straightforward as this may sound, observations of professional practice suggest that scaffolding defined in these terms can be a challenging responsibility. The reason seems to reside in the demand for diagnosing a student’s momentary needs in sufficient depth to allow meaningful contingent interventions (Graesser and Person, 1994, Palincsar, 1986; Wittwer, Nuckles, Landmann and Renkl, 2010). This difficulty is rendered more troublesome when the diagnoses a tutor makes are carelessly transferred between different learners. For example, procedures which worked with novice learners can be disadvantageous when transferred to learners with higher levels of expertise: a finding sometimes termed the ‘expertise reversal effect’ (Kalyuga, Ayres, Chandler and Sweller, 2003; Schnotz, 2010)

The second scaffolding principle is ‘fading’. This is also an overarching strategy: one that involves acting to reduce tutorial guidance as the learner demonstrates more and more competence. Ultimately this may converge on what is termed a ‘transfer of responsibility’. Fading is an important principle both for managing traditional tutorial interactions but also for the design of written instruction: i.e., materials that are encountered within private study rather than conversation (e.g., McNeill, Lizote, Krajcik, and Marx, 2006). This last observation hints at a versatility in the vocabulary of ‘scaffolding’: it can be applied to a textbook and not just instructional designs featuring a co-present human tutor.

Scaffolding, as outlined here, seems to be quite hard work. How can the investment be justified? That is, how can we evaluate the effects of that investment? The question about scaffolding ‘effects’ comes in two forms, the first – rather less interesting – concerns what are the effects with scaffolding. In that case, we may simply want reassurance that some task can be solved by a learner with the support of scaffolding. A scaffolding may thus be a useful routine whose outcomes may diagnose a learner’s degree of readiness for understanding certain material. Yet, simple task completion remains only a modest criterion for the efficacy of scaffolding, not least because the support that was provided can potentially range so widely – variously mild or intense. On the other hand, what a learner can do with support – effects with – may, for a teacher, still provide a useful assessment of that individual.

The second framing of an efficacy question addresses the effects of scaffolding. That is, lasting effects. An impact apparent beyond simply completing the scaffolded task. This requires testing the learner sometime later and on new tasks, now performed unaided – where learner independence has been made the goal of a scaffolding encounter. The significance of such research depends on the choice of those post-intervention tests. If they are merely minor modifications of the original task, then success will be less compelling. More impressive would be success on tasks whose design probes deeper, and into more general achievements of domain understanding. Howe (2013) discusses this stronger demand and reviews studies where such generalisation of scaffolded learning has been reported.

The articulation of tutoring in terms of scaffolding processes has proved engaging. It may have stimulated a flurry of research on the efficacy of tutoring more widely. Such studies contribute a probing extension of the evaluation research reviewed by Bloom (mentioned at the start of this chapter). However, tight evaluation studies are hard to design because, although there is a agreed template for this interactions, the exact choice of how its delivered has to rest with the participants. The researcher’s instructions to a tutor are bound to respect this open-ended character and this will not allow control over some singular style of communication for evaluation. Nevertheless, meta-analytic and systematic reviews of such research studies do indicate that outcomes of scaffolded tutoring are reliably positive (e.g., Mermelshtine, 2017; Van de Pol, Volman and Beishuizen 2010; VanLehn, 2011).

These observations of tutoring processes add depth to Bloom’s efficacy claims for its efficacy as made at the very start of this chapter. Bloom’s (1984) 2-sigma statistic has been a cornerstone of evaluation research in this field. However, his was an assertion about efficacy partly built upon unpublished doctoral research by Bloom’s own students. Unfortunately, a close analysis of those studies indicates design shortcomings that may not justify the full force of conclusions drawn – well-intentioned though they may have been (VanLehn, 2011). Taking this into account, and considering other more recent evaluation research, VanLehn proposes that tutoring impact is real but with a mean effect size of 0.79 (rather than 2.0) is a more appropriate judgement on the efficacy of tutoring. Of course, this remains a substantial effect.

The terms ‘tutoring’ and ‘scaffolding’ are often used interchangeably. This elision may upset the purist who will insist that ‘scaffolding’ should apply only to the systematised version of tutoring first set out by Wood, Bruner, and their colleagues. However, a scaffolded encounter comprises a mix of ingredients – within any given occasion some will be exercised more vigorously than others. So, the purist cannot realistically demand that this term is reserved for some canonical version of the interaction. The reason research centred on scaffolding has been valuable is not because it has forged rigid proscriptions for a fixed learning practice. Its value has been to define a structure within which individuals can construct a learning pathway that is tailored to the circumstances of participants, setting, and problem tackled.

Considerable research interest in talk adopted during scaffolding is unsurprising. It is certainly a rich topic for investigation, not least because the challenge for tutors to guide learners with the strategies of subtle indirection can inspire much conversational ingenuity. Tutoring partners are often highly creative over the prompts and questions that serve to hint, nudge, provoke or inspire – rather than to direct. Even so, the brief coverage of evaluation studies in the present chapter section did not dwell on exactly how variations in tutoring discourse skills might predict variation in learning outcomes. Why this neglect of what seems an obvious theme? The reason is that doing so would have shifted our current focus more towards ‘acts of teaching’ rather than ‘acts of learning’. However, a closer look at the internal dynamic of tutoring will be taken up in the following section: it considers what the learner must bring to tutoring in terms of established confidence in appropriate dialogue practices.

3) Being a guided learner

Everyday references to ‘tutoring’ can risk fostering the idea that it is something ‘done to’ learners (“I had to tutor him in maths” etc.). Yet it is more a matter of participation than imposition. Hopefully, learners are not generally forced into dialogues of the kind sketched above; hopefully they will be gently seduced there. Moreover, learners may themselves chose to initiate them. There is always an agency required of the learner – if tutoring is to go well. So, as with all learning acts, we must ask: what dispositions should individuals bring to this learning opportunity such that it functions effectively for them. What forms of ‘learning agency’ does it expect of learners if it is to successfully support their needs, or satisfy their curiosity?

From what has been said in the last section, it would appear that at least the following dispositions are important. First, the learner should regard other people as resources through which their own knowledge may be extended. Second, in any given situation they should recognise which particular people might best fit their needs at that moment. Third, they should be able to express their curiosities through the asking of questions and recognition of responses. Finally, albeit ideally, the resulting dialogue should be held as a stimulus for future reflections: tutoring imparts a legacy that stimulates future and further explorations.

This last point is significant. It is common and proper to insist that dialogue should be a process of mutual knowledge construction – that is, not simply the delivery of well-formed and final answers. So, it is especially valuable if the knowledge acquired becomes a platform for later and independent thinking about fresh problems. What is thereby learned becomes a resource that inspires exploration beyond the occasion of a tutoring episode. Taken all together, these considerations imply the following about how learners should enter acts of tutoring. They should come with an openness to collaborate with others, a confidence to participate in an inquiring dialogue, and a willingness to recruit dialogue as a legacy for further and future reflection.

All of which encourages reflection on the origins of such capabilities. How far are these forms of tutoring agency are apparent in the earliest years of life? How and where are they rooted? As was argued above, developmental psychology research can often allow us to see more vividly the foundations of a psychological function. Once rendered visible, we may then suggest a research agenda for understanding adult learners, or for those growing up in different cultural contexts.

Independent exploration is manifest during a child’s first two years. Moreover, such exploring can be organised by infants in an apparently hypothesis-driven manner (Gopnik, 2012). In other words, a native curiosity motivates the closing of “information gaps” that infants experience in their relationship with the world (Lowenstein, 1994). Yet, fully meeting this curiosity will benefit from recruiting the support of available caregivers. An awareness of such possibilities is present very early in life. Studies show that by 2 years of age, when children are experiencing the need for help, they reliably direct their gaze towards available and friendly adults. Questioning has roots prior to a capability for language; it may occur within infant gestures or facial expressions. For example, Chouinard, Harris and Maratsos (2007) detected such non-verbal strategies in a set of diary records kept by the mothers of children aged between 1 and 5 years. Although in the first two years they are not yet directing this attention to others in a systematic way. That is, they do not always turn to those helpers whose knowledge is best matched to the difficulty they are confronting (Goupil, Romand-Monnier and Kouider (2016).

In the later preschool years, children sharpen the manner in which they appeal to others. In particular, the emergence of language means that they can address those around them with more explicit forms of inquiry. Growing confidence with verbal communication means the act of questioning can not only become more precise, it can also become more organised. For example, Frazier, Gelman and Wellman (2009) interrogated a large research database of children’s early recorded conversations (the CHILDES project) to reveal how older pre-schoolers will increasingly persist in questioning when they do not get answers that match their needs. In other ways these help-seeking questions become more strategically applied. So, in a problem-solving situation, children typically hold back on asking questions until they experience uncertainty about what they should do next in the situation. Similarly, while they may seek help if a puzzle seems to them difficult to solve, they are less likely to do so when a puzzle is similar to ones that they recognise they have successfully solved earlier (Was and Wameken, 2017).

Nevertheless, a number of studies demonstrate that pre-schoolers regularly underestimate the extent of their need for help in problem solving situations (e.g., Vredenburgh and Kushnir, 2016). Moreover, this is not entirely egocentric. So, if children at this age hear a story about another child solving a problem with adult guidance, they will also overestimate how far that child is responsible for the successful outcome (Sobel and Letourneau, 2018). This is a reminder that effective tutoring depends on realistic self-diagnoses of where others are important to one’s progress. This can be slow to develop optimally.

Ronfard, Zambrana, et al (2018) have reviewed a large body of research concerning elementary school age children’s question asking. They conclude that in the period between 6 and 10 years of age, children generally will be formulating clearer questions and reasoning about evidence more effectively – thereby more accurately targeting the questions that they pose. They will also remember the answer to questions that they have asked, more than answers they have heard given to others. Within the context of tutoring, precision of questioning is evidently important, but so is the learner’s processing of answers given. More strategic engagement of that sort is also observed in the school years. So, in a study of children aged between 4 and 7 years, Cottrell, Torres et al (2023) found that the older children more often expressed open scepticism about an adult’s claims when those claims were made to be surprising or unlikely. And they were more likely to suggest exploration possibilities appropriate for testing out the claims that they heard. Similarly, Dannovitch, Mills e al (2021) report that within the age range 7-10 years, children were increasingly motivated to further inquiry when given explanations that were intentionally designed to be incomplete answers to their questioning.

These research reports indicate a very early receptivity to the pattern of communication that underpins tutoring. Yet the fluency of mobilising tutoring dialogue as an act of learning continues to develop well into childhood. Learners may seem to understand the nature of the ‘tutorial contract’ from an early point. But understanding the general form of a contract does not promise fluent engagement with its opportunities. So there seems a continuing challenge for learners to frame their tutoring questions at appropriate depth – apparent even for undergraduates (Graesser and Person, 1994). That study also revealed shortcomings in how effectively students provided feedback about their own shifting understanding as a tutoring session progressed. The authors comment on their findings: “Students frequently answer ‘Yes’ when they fail to understand the material because they want to be polite, because they want to avoid appearing ignorant, or because they are unable to detect their lack of understanding. Tutors often accept this feedback, assume the student has mastered the topic, and move on to another topic” (132).

It must be hoped that well-crafted patterns of whole-class discourse will be helpful in modelling for such students the tactics of dialogue questioning. Moreover, it has recently been suggested that this kind of confidence can be cultivated through interacting with computer-based pedagogical agents; these require users to generate questions that they suppose would lead to good answers to various propositions the system provides (Alaimi, Law, Pantasdo, Oudeyer and Sauzeon, 2020).

Evidently the key agency that learners bring to tutoring is how they pose timely questions and how they build upon responses to those questions. Such dialogues are characterised by an indirectness on the part of a tutor, a style to be contrasted with those more didactic methods whereby information is ‘directly’ transmitted, or perhaps exchanged in single IRF sequences. Such indirectness is typically motivated by recognition that learners should gain ownership of the knowledge that emerges; in other words, that tutoring should facilitate a degree of knowledge construction. Yet there is a tension here: one that arises from tutor/learner partners necessarily differing in their knowledge-bearing status. The learner must recognise a format for interaction that the tutoring ‘contract’ requires. In particular, that the response from their tutoring guide need not imply inquiry closure. But, also, that the learner’s frank and accurate feedback on emerging understanding is something expected by that guide.

Being a skilful participant within the tutoring contract is evidently a big challenge. Nevertheless, it is important to stress that recognition of the contract and what it requires is present very early in life. Young children understand how the format of questions and responses can have a fluid, open-ended, or incomplete quality. There is evidence that parents of pre-school children frequently exercise the open-ended questioning of this ‘tutoring contract’ (Yu, Bonawitz and Shafto, 2019). Those authors describe parental exchanges of this sort as “pedagogical questioning”. Given that it is so widely applied, it must surely have been perceived to work. In which case, even very young children must be presumed comfortable managing the following two tensions: why they are being asked questions by others who are clearly knowledgeable, and why those same informed others sometimes give incomplete answers to the child’s own questions.

In other research (Yu, Landrum et al 2018), the learning consequences of preschool children’s differing responses to this domestic and pedagogical questioning were evaluated. This involved studying whether the indirect questioning strategy was as effective as direct instruction in transferring information. In their study this involved information relating to a child’s interest in the functioning of a toy. First, pedagogical questioning was shown to be as effective as direct telling for achieving understanding. And, second, it was shown that such ‘indirect’ instruction did not – unlike direct instruction – discourage children’s further and independent exploration of the toy. Moreover, when questioning about the toy’s functioning was by a naïve adult observer (i.e., someone who clearly did not know how the toy worked), then the questions asked by those adults were less likely to be successful as instruction. So even though the questioning could be understood as ‘pedagogical’, the children understood that this did not fit what they knew about the speaker.

These authors suggest that their pattern of results indicates that even very young children could actively “infer an intention to teach” in others. Such a conclusion complements claims made elsewhere that a sensitivity to the existence of pedagogical communications may be a distinctive characteristic of the human species (Csibra, 2007; Csibra and Gergely, 2009). The tutorial contract is recognised at the start of life and is variously cultivated as experience grows. It is reasonable to suggest that one consequence of research on tutoring as an early act of learning is that it has given credibility to this important claim. The claim is important both because it suggests our inherent sensitivity to the signals of intended pedagogy. But also, because the existence of such sensitivity invites research on how it is then elaborated – through increasing participation in occasions of interactive pedagogy.

4) How tutoring works: distributed cognition

To summarise: learners recognise pedagogical intent in others and, equipped with that awareness, they seek out (or accept invitations into) exchanges that become ‘tutoring’. The range of contexts and topics for which tutoring can be organised is very wide – as close reading of the research methods employed in studies discussed above will illustrate. However, an impression conveyed by those examples is that the basic frame for a tutoring episode is something well-established within childhood and reproduced relatively intact beyond. Of course, it will become populated by new kinds of problems to be solved, and the richness of the dialogue will be greater. This simply follows from the spread of its application but, also, from the growing communicative confidence of learners. Yet, at their core, these episodes comprise a recurring choreography of interaction, within which – at its best – a learner can gain credible responsibility for, and credible ownership of, emerging understandings. That learning happens this way is evident, but we surely need to know how it happens.

Consider a problem being addressed by a learner acting alone – perhaps in a maths or science classroom. Most cognitive psychologists would analyse this situation with the language of information flow. The learner’s progress will be a matter of directing perceptual attention and recruiting or updating information in memory; while using that evolving pattern of gathered information to make inferences, to reflect, to predict, to generalise, and so forth. Unfortunately, most of this computational effort is hidden from the researcher. The functioning of a private mental apparatus must be inferred from modest traces available in the learner’s observed behaviour (including their verbal self-reporting, if that is requested). However, in this chapter concern has not been with learners acting alone but with tutoring, a social act of learning. That entails learners participating in what may be termed a learning system: an intimate context for problem solving that involves multiple actors.

In situations where people are not problem-solving alone but are together – such as in tutoring – the equivalent thinking dynamic is often theorised as a process of ‘distributed cognition’ (e.g., Brelland, 2011). In solitary thinking, the sources of, and the flow of, relevant information is the responsibility of the individual, as is the executive function that oversees this. But in a tutoring situation, these matters of attending, memorising, reasoning etc. are ‘distributed’ – i.e., they are shared among, or exchanged between, the partners tackling a problem together. In acknowledging the possible distribution of thinking in this sense, many psychologists have conceptualised cognition as something that invariably is ‘externalised’ (Clark and Chalmers, 1998). Addressing such acting-within-the-world as thinking indicates the way in which cognition can be termed ‘distributed’. Altogether, this has prompted a shifting of effort within cognitive psychology from asking “what is inside the head?” towards also asking “what is the head inside of?”

Within tutoring, what the head is inside of is basically a social practice of talk and action. But tutoring may also locate the head within a mix that includes thinking technologies; such as digital tools of calculation or memory. And the mix may include other material elements characteristic of the problem-solving environment: that is, designs for optimising the space-of-action, and tools that mediate what gets done in that space. Framing cognition in these terms – distributed into the environment – renders ‘thinking’ as a form of dialogue: one in which the mind is in conversation with the material (Fernyhough, 1996). A practical example may bring into better focus how the external world ‘props’ the cognition of tutoring. Consider the ubiquitous jigsaw as a tutoring context. Jigsaw thinking may be effectively supported by those trays that enthusiasts often use to categorise and order their pieces. So, such a material example may also be regarded as part of a problem’s ‘scaffolding’. Or, expressed in the current vocabulary, they are an environmental element through which thinking gets distributed. The challenge to choreograph effective tutoring then becomes a matter of configuring a space witin which thinking can be externalised both socially and materially.

Many regard these developments within cognitive psychology as refreshing. First, because distributed cognition highlights social interaction in the mainstream of accounting for thinking and problem solving – a theme previously neglected. But also, because the vocabulary for theorising human cognition has shifted still more radically than that: our practices with external tools and within environmental designs becoming part of how human intelligence itself is now to be theorised. Notepads, calculators, and knots-in-handkerchiefs all support cognition by the ways in which they mediate our remembering and reasoning.

Evidently, this emerging vocabulary of cognition as ‘distributed’ fits snugly with tutoring. There are clearly desired outcomes that are defined as ‘effects with tutoring’ – that is, problems do get completed, answers do get found. So, understanding this success can be theorised as the consequence of creatively distributing the thinking required by a task. That is, distributed between people, but also between people acting with available external resources for thinking, with ‘mediational means’. Finally, this resonance between theory and practice appears to complement well the influential theorising of Lev Vygotsky (1978) – a Soviet author writing in the 1930s (but translated only more recently – hence the misleading authorship dates).

Two central themes in Vygotsky’s work are particularly relevant to tutoring. The first is the proposal that all learners inhabit a ‘zone of proximal development’ (ZPD). For a given problem, this zone defines a conceptual space between what the learner can achieve unaided and what they can achieve with support. Or, more exactly: “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance, or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86). Evidently, tutoring as described in this Chapter could be considered a process for mapping an individual’s zone of development. A learner’s tutoring trajectory could thereby become part of their cognitive assessment. This direction of theorising offers an attractive descriptive account for tutoring outcomes of the ‘effects-with’ variety: learners in this zone are indeed taken beyond their unaided capacity by the techniques of distributing cognition. Moreover, there is a credible assumption that where tutoring entails a fading of support (as strict ‘scaffolding’ requires it should), then the functions of a withdrawn tool/guide can be taken over by the learner independently. If fading is successful then this is likely to be what is happening. Whether such take-over is reflected in longer term learning gains (‘effects of’ tutoring) remains an assumption. So, at least the ZPD describes an umbrella under which these ‘effects-with’ achievements occur. But in relation to longer term learning outcomes of the ‘effects-of’ variety, ZPD remains more descriptive than explanatory.

We naturally remain anxious to explain learning in ‘effects-of’ terms: i.e., learning that is deep enough to be manifest in success on tasks beyond that which was tutored. This is more usefully addressed by the second theme derived from Vygotsky’s work: namely, the ‘internalisation’ of cognition. It is captured in the following assertion: “Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first, between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological)” (Vygotsky, 1978, 57). In other words, while we may bring to the solving of problems a private mode of thinking (the ‘intrapsychological’), such internal processes of reasoning and remembering have their origin in thinking that has elsewhere been done by us collaboratively (the ‘interpsychological’). In this way, Vygotsky’s ideas invite us to consider learning that arises from tutoring as a consequence of successful internalisation: meaning that learners appropriate into a private mental space capabilities of reasoning and remembering which were previously enacted during externally distributed thinking. Such processes of internalisation are attractive for explaining the positive outcomes of learning by tutoring – the ‘effects of’. Certainly, it is a form of explanation that is frequently invoked. Yet, as an explanation, internalisation remains more often pleasingly inferred, than confidently demonstrated.

Vygotsky’s theorising on learning is often termed ‘socio-cultural’ and this fits well with perspectives that highlight the distributed nature of cognition. For it signals a view of cognition as something arising from interaction with others (such as tutors and peers) but also it considers cognition to be effort mediated by cultural tools (many of which are in the external world, such as notepads, calculators and knots-in-handkerchiefs). None of this demands that cognition and learning are radically social – in the sense of it inevitably needing to be exercised with, or among, others. Cognition may be asserted inevitably ‘societal’ (arising from group living) while not being narrowly ‘social’ (arising only within interpersonal exchange). Similarly, it’s concern with cultural forces is not radically constraining either. That is, it does not deny the idea that the act of reasoning can involve exclusively in-the-head processes. But it does insist that acts of learning and cognition have their origin in the individual’s socio-cultural ecology – and that they continue to evolve there through integration of social, material and mental circumstances.

5) How tutoring works: cognitive load

The distributed thinking that characterises tutoring has been addressed by a second theoretical tradition also concerned with tutoring ‘effects’: namely, CLT or cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988). First, a sketch of that theory itself and then a consideration of its ‘fit’ to explaining how tutoring works.

A necessary starting point is the widely-accepted architecture of human memory. This comprises, first, a component termed long-term memory (LTM) which is for organising and storing large bodies of information, and, second, a limited-capacity, short term or ‘working memory’ (WM), which handles transient and small amounts of information. The latter has two modality-specific sub-systems whose management is highly significant for CLT: namely, a visuo-spatial store and a phonological store. These deal with, respectively, visual and verbal inputs to the cognitive system. Thereby the working memory acts to create visual or verbal models which a learner may then integrate with material existing in their long-term memory. It is relevant here to acknowledge a body of research that has found correlations between individual working memory performances and measures of cognitive or academic functioning (e.g., Conway and Kovacs, 2013; Ellingsen, Engle and Sternberg, 2020).

CLT asserts that a significant challenge during learning is one of optimally managing the information flow that this mental apparatus supports. The tasks taken on in support of learning will impose various kinds of load on this cognitive system (Sweller, 2010). First there is an intrinsic load. This arises from the inherent structure of a task problem. For instance. it may have a greater or lesser number of interacting elements that have to be managed at the same time. This creates more or less of a load on mental computation. It may be moderated by the prior learning brought to the task but it cannot be moderated by instructional treatments (although this is debated (De Jong, 2010). It is intrinsic to demands of the task. Second, there is load that is extraneous. This does concern instruction, or how the material is presented for learning. The design of instruction creates its own load, perhaps by being confusing, over-complex or a source of irrelevant distractions. Finally, a task will create germane cognitive load which arises from the constructive work carried out by the learner solving the task problem. As that effort of construction – and the fruit that it bears – are exactly what is intended by tutoring, it follows that task design should effectively stimulate the germane cognitive load necessary to be creative in this manner.

The terms in which the distributed cognition of tutoring has been presented above might seem well matched to the terminology of CLT. Moreover, the metaphor of ‘load’ surely seems to fit our intuitive feeling that learning is often hard work. Given that understanding, what a supportive tutoring environment achieves can then be regarded as an effort-reducing distribution of learning ‘load’. Indeed, there is no shortage of empirical research studies on tutoring that invoke CLT in just this way (e.g., Brelland, 2011; van Nooijen, de Koning et al, 2024). Such studies tend to claim the learning success of procedures such as scaffolding arise from it being a design for instruction that minimises the consequences of extraneous cognitive load.

Surprisingly perhaps, this research is matched by other studies that invoke CLT to justify a scepticism about such tutoring techniques – promoting in its place a method of ‘fully guided’ instruction, rather than the ‘minimal’ (or indirect) guidance characteristic of scaffolding (Sweller, Kirschner and Clark, 2007). This scepticism is based on an expectation that elaborate investments in tutoring dialogue risk the creation of distracting, unnecessary, or ‘extraneous’, cognitive load (van Merriënboer, Kirschner and Kester, 2003). Yet this danger may be merely something to guard against rather than an inevitability. Indeed, de Jong (2011) identifies a number of ways in which the guided instruction of such designs as tutoring need not be a source of extraneous load at all – if suitably anticipated. One example of anticipation might be learners externalising their cognition in ways that counteract extraneous load from the intrusions of tutoring. For example, they might take notes on their progress: limiting load by offloading onto paper the demands of mental computation. On the other hand, perhaps such learner-generated externalising moves are inhibited by the presence of a tutor. Such interactions remain to be studied. Evidently, the dynamic of distributing cognition is subtle and there is still much to understand regarding how it is optimised.

6) How tutoring works: self-explaining

In the typical investigation of tutoring, a learner is invited to solve a problem under the guidance of another person. If that problem is solved, then productive thinking has occurred during the journey to success. To some extent the thinking will have been public and shared. While, to some extent, there will also have been thinking that is private and personal. Being able to complete a problem with tutoring is gratifying. But the nature of any lasting impact of that success may be uncertain – until that consequence is tested for. As laboured in the discussion above, the most pleasing outcomes of tutoring are always those where effects with are followed up by effects of. Such ‘effects-of’ are revealed by finding successful outcomes achieved on fresh versions of the problem tutored. Although, most pleasingly, by finding successful outcomes achieved for totally new problems – but ones recruiting similar conceptual understandings as those required in the tutoring.

One recurring theme in analyses of tutoring interactions is what might be termed the ‘construction imperative’. This amounts to a strong expectation that the learner’s experience should facilitate their active involvement in the construction of fresh understandings – rather than the passive receiving of them. Tutoring should cultivate the learner’s sense of owning new understandings; a sense that their own actions are significantly responsible for the insights that emerge. This requires consideration of how these ‘understandings’ – these cognitive outputs of learning – should be characterised. Such products of learning are conceptual in nature. They refer to abstract structures of knowledge that, through learning, have been made available as fresh, or revised, tools for the learner to think with. But what exactly does a constructing learner do that might bring about these cognitive outputs? One way forward might simply be to ask them – although, ideally, asking them at the time that this construction is underway. That would require some form of think-aloud procedure during learning.

Chi, Bassok et al (1989) reported a study of just this kind. They invited undergraduates to a research lab to work individually during sessions spanning several weeks. The students tackled physics problems during which they were asked to think aloud. They all started with similar levels of understanding the material. But post-intervention testing revealed that good students (i.e., those who post-tested well) had studied the materials “by explaining and providing explanations for each action…their explanations refine and expand the conditions of an action, explicate the consequences of an action, provide a goal for a set of actions, relate the consequences of one action to another, and explain the meaning of a set of quantitative expressions” (1989, 176). The authors termed this cognitive practice “self-explaining” and since that time it has proved an influential idea within explanations of the learning process.

In a later study, Chi, de Leeuw et al (1994) explored the possibility of actively encouraging such self-explaining. Without prior training, secondary school students were prompted to do so while reading a text on the human circulatory system. Their subsequent understanding was compared with a reading-only control group. The self-explaining students displayed a greater “ability to answer more complex questions” (p.470). Moreover, these students possessed more advanced mental models of the biological system studied. The apparent value of self-explaining as observed in contexts of private study must suggest exploring its place within tutoring. Chi, Siler et al (2001) approached this through a project on undergraduates studying material with tutors who were asked to adopt different styles of tutoring. These were variously didactic or prompting, but also included a condition in which tutors were asked to withhold their explanations and feedback. An unexpected outcome was that tutored learning was just as effective when explanation and feedback were suppressed in that way. This would imply that the success of tutoring does not simply come down to the tutor’s skills of questioning and confirming. It may be more a matter of creating an interactive space that fosters for students a constructivist relationship to the studied material.

This leads researchers to cast self-explanations as outputs of construction; thereby comparing them with more traditional thinking outputs, such as concept maps, notes, or specific hypotheses. And as with those outputs, a self-explanation can be usefully generative. As expressed by Chi (2009): “the point is that the outputs, once externalized, become new materials from which a student can examine and infer further new knowledge” (p.79). Thus, a self-explanation can be creative (or ‘constructive’) in that sense: it can provide a means to configure and re-configure mental models for the subject domain that the learner is studying. Within cognitive psychology, this kind of knowledge object is often described in the language of ‘schema’. In this tradition, understandings of the world are organised into schematic knowledge structures. Their construction and subsequent elaboration arise from the learner’s cognitive activities of ‘working’ the material studied: interpreting, classifying, generalising, exemplifying, and so on. Once constructed, schemas are strengthened or modified in these ways at times of their later retrieval. The role of self-explaining within such activities makes it a key practice of constructivist learning.

A striking suggestion from research reviewed above seems to be that what counts in tutoring is not so much what a tutor says but their responsibility for creating a shared and sustained dialogue space. These findings seem reinforced by a further series of projects in which some learners were placed within tutorial spaces and others were invited to observe them. Chi, Roy and Hausmann (2008) organised 70 physics undergraduates into five learning groups: a one-to-one tutoring, collaboratively observing that tutoring, observing that tutorial alone, collaborating on the problem, and simply studying alone. In their summarising words: “…the results showed that students learned to solve physics problems just as effectively from observing tutoring collaboratively as the tutees who were being tutored individually” (2008, 301). This finding was further replicated in a related study (Chi, Kang and Yagmourian, 2017). Interpretations of such research do not undermine the value of tutoring. The tutoring dialogue in these studies certainly works for tutees (in comparison with untutored methods). But its impact is extended when it becomes itself an object of a second (external) dialogue among a collaborating student pair who are its witnesses. Again, the favoured explanation for this is the enhanced opportunity for (now collaboratively) self-explaining the tutoring that is being witnessed. Among other things, a self-explaining of the self-explaining!

Some caution is required in the extent to which all of these studies are generalised. Often the participant samples are small and the range of educational contexts researched is narrow. Moreover, the effects of tutorial-watching may be fragile (Muldner, Lam and Chi, 2014). Ding, Cooper et al (2021) find that learning from witnessing tutorials is more likely to be an advantage for students with existing knowledge in the observed domain. Moreover, attempts to embed these ‘vicarious learning’ experiences in an authentic class may not be welcomed by learners. Cooper, Ding et al (2018) report surveying undergraduates in such a class and finding that instructor-only videos were preferred and enjoyed more than instructor-tutee tutorial videos.

The “explain” in “self-explaining” should not be taken to literally. Otherwise, it may be misleading. So, it should not imply the kind of measured clarity of expression that might occur if a learner was explaining ‘out loud’ – especially, to a critical listener. It is a generic term. Although these three broad forms of thinking are involved (Chi, Bassock et al 1989): filling in missing parts of a phenomenon not yet fully understood, integrating new knowledge with old, and resolving cognitive conflict when misconceptions become apparent. Embedded within this may be acts of, say, inferring, or generalising, or hypothesising, and so on. It is a useful concept; because it characterises the learner’s mental engagement in active terms: a conscious effort of ‘explaining’ to self. It has also been effectively adopted in classroom contexts (Dunlosky, Rawson et al 2013). Evidently, there is always more investigation required to reveal the exact contents of the learner’s ‘explanations’ on any given occasion of problem solving. Sadly, it is beyond the scope of this text to explore how the observed contents of such mental conversations relate to the particular design of the problem being tackled. But that is a realistic project.

Self-explaining is an important concept to emerge from the work of Chi and her colleagues and it will be re-visited in various guises provided by the chapters that follow. However, this research group also stress another common feature of their observations. That is the extent to which the tutor’s investment in jointly constructing meaning was more effective than their simple provision of task-related information. While the necessarily improvised nature of tutoring dialogues makes systematising this difficult, there is an element of social harmony or social convergence that is important to identify and understand. This is considered in the following section.

7) Co-construction, intersubjectivity and robots

At the start of this chapter, it was observed that the term ‘tutoring’ applies to a wide spectrum of relationships. This width relates to content, form, and membership. So ‘tutoring’ has to embrace the intimacy of a child and caregiver in guided play, as well as the reluctance of a secondary school student confronting algebra. Research designs do address this diversity but, thereby, they report a mix of findings – uncertainties that may not fully satisfy practitioners. What does remain clear is that tutoring can be a very powerful arrangement for learning, one that is applicable across all configurations of learners. It furnishes a special kind of dialogue space. One which, at its most productive, can animate the learner towards actively configuring and reconfiguring what they know. In the discussion above we suggested that this animation works through a cognitive process usefully summarised as ‘self-explaining’. Which, in turn, arises from participants successfully managing a distributed arena for reasoning and memory

Some researchers refer to productive activity in this dialogue space as ‘co-construction’. Chi (1996), in summarising some of her own research, illustrates this as follows: “Co-construction is having the adult tailor the task in a way that allows the child to perform successfully …The tutor’s goal can thus be seen as trying to get the tutee to share the tutor’s knowledge and understanding (through scaffolding), rather than to create or negotiate a shared meaning which neither one originally possessed” (37-38). Some observers of tutoring elaborate this concept of co-construction by invoking a ‘convergence’ of thinking (Sinha and Cassell, 2015). This may happen as participants gain awareness of what is sometimes termed the “common ground” necessary for effective communication (Clark and Schaefer, 1989). ‘Convergence’ hints at the idea that partnered human beings may have a natural capacity – and appetite – for achieving synchrony within mutual action (Zicha-Mano, 2024). Sinha and Cassell (2015) seem to suggest this when appealing to the importance of ‘rapport’ in tutoring. ‘Rapport’ is important here. Although in educational psychology, it may be more often invoked through the technical vocabulary of ‘intersubjectivity’. This important term will recur when considering other acts of learning in this book, so it deserves elaboration here.

Consider it this way: you and I experience psychological states – subjectivities – by virtue of us being conscious human beings. We feel variously happy, sad, anxious, alert, and so forth. ‘Intersubjectivity’ then refers to circumstances in which my subjectivity is brought into a relationship of reciprocity with yours. This may readily occur during the course of our joint activity. Wherein it becomes psychologically important, at least if it is then mobilised towards the productive management or oversight of our activity. This may happen if my awareness of your psychological state (frustrated, puzzled etc.) leads me towards actions that you may find useful (reassurance, guidance etc.). Of course, under less friendly circumstances, it may also lead me into unhelpful actions (mockery, neglect etc.). This disposition to recruit intersubjectivity – empathically or otherwise – is said to arise from us exercising a ‘theory of mind’ (Premack and Woodruff, 1978): simply put, an ability (and appetite) to interpret the possible psychological states of other people. This capacity is one that is widely assumed to be uniquely human (Tomasello, 2009), it is present in a simple form from an early age (Trevarthen and Aitken, 2001), but richly elaborated during a child’s development (Rakoczy, 2022).

As might be expected, intersubjectivity has become a significant explanatory concept within the psychology of learning – indeed, within educational theory more widely (Beraldo, Ligorio and Barbalo, 2018). In the context of tutoring, it is surely a very valuable human capability. After all, to achieve a richness of co-construction, both partners constantly need to exercise intersubjectivity: to anticipate, interpret, evaluate and endorse the actions of the other. This entails reading those actions through a private ‘theorising’ of the other’s emotional and cognitive state. Inevitably, what is read will be a moving target. So, the sheer effort of such online ‘theorising’ should not be underestimated. Perhaps it is what accounts for the fatigue that can be so common for those who work on learner guidance within tutoring contexts.

For this (and many other reasons) there is much interest in whether tutoring is a one form of social learning that can be supported instead by machines. Scepticism about how far this might be possible is partly a matter of whether the intersubjectivity so important to tutoring is considered a distinctively human capacity. The pioneers of scaffolding were early to reflect on this: “Where the human tutor excels or errs, of course, is in being able to generate hypotheses about the learner’s hypotheses and often to converge on the learner’s interpretation. It is in this sense that the tutor’s theory of the learner is so crucial to the transactional nature of tutoring. If a machine programme is to be effective, it too would have to be capable of generating hypotheses in a comparable way” (Wood, Bruner and Ross, 1976, 97). Intersubjectivity seems to be the capability suggested by these remarks, although not named. Yet the informal term ‘rapport’ may be more usefully vivid than ‘intersubjectivity’ – at least if it invites deeper theorising of the very subtle human interaction characteristic of effective tutoring.

Yes, the progress of learning must certainly depend on the kind of cognitive hypothesising Wood and colleagues refer to. But it also depends on the trust and engagement that arises from the depth of the relationship experienced by tutoring participants. That is a challenge for any mechanisation of the process.

For example, Kennedy, Baxter and Belpaeme (2015) describe the interaction between 7-8 year-old children and social robots programmed for tutoring prime numbers. The robots maintained a tutorial conversation but in one condition a robot interacts in a personalised way (uses children’s names and applies gaze contact more appropriately), in contrast to a ‘asocial’ robot who does not do these things. The tutoring was successful but less so for the social robot. It would appear that the personalised attitude of the social robot acted as distraction: it was more likely talked about as a friend by the children (while in the asocial condition children more often referred to the robot as a teacher). This is not an argument for the counter-intuitive strategy of not personalising robot tutoring interactions. But it is a reminder that designers face a significant challenge in predicting how human learners perceive the agents of intelligent tutoring systems (ITS). A similar reminder follows from a study by Ogan, Finkelstein et al (2012). These authors describe an ITS supposedly built with peer rapport. The system remained adamantly polite throughout tutoring. Yet from observing actual human peer tutoring, these authors point out that: “Though most intelligent tutoring systems that attempt to build rapport with the learner do so through politeness, actual peer tutors employ a great deal of impolite and face-threatening behavior.” Creative impoliteness is a resource that often depends on judgements built upon a long history of interacting with the other. Moreover, the way in which it is most effectively applied within tutoring may shift across the course of the episode.

These considerations suggest a challenge for ITS design – inevitably so if intersubjectivity and the theorising of mind really are distinctly human capabilities. Yet, as might be expected, there are authorities who believe that such capabilities are culturally acquired rather than biologically granted (Heyes, 2018). That is a debate that remains ongoing (Nichols, Moll and Mackey, 2022). In whatever direction it may come to be resolved, at the time of writing there is increasing optimism regarding the application of artificial intelligence to ITS construction – including designs in which the management of intersubjectivity is taken seriously as a goal (Orega-Ochoa, Arguedas and Daradoumis, 2024). MetaTutor is one example (Azevedo, Bouchet et al 2022). While recent reviews suggest that progress has been made quite widely; albeit largely in STEM subjects and largely with college students (Paladines and Ramirez, 2020; d’Mello and GRaesser, 2023).

8) Culture and context

There is a large corpus of research that addresses tutoring as an act of learning. Only its surface has been skimmed in the present chapter. Consistently, that research finds positive outcomes for tutoring, and also seems to document its pervasive presence inside and outside of formal education. All of which is likely to leave an impression that the practice of tutoring – as defined here – is ubiquitous, inevitable, and natural to the human condition. However, all of such claims need to be carefully qualified. Not least because most of the present research corpus is culturally specific. Not that this situation is unique to the case of research on learning. Arnet (2008) reported a general survey of studies published in the leading psychology journals: 96% of research participants were from economically-developed Western countries – within which just 12% of the world’s population lives. In short, scholarly findings on tutoring will chiefly apply to the anthropologist’s WEIRD communities (western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic).

Research on children’s learning outside of WEIRD is considered by experienced commentators to be scarce (Legare, 2017). However, what is said in that research does not allow the assumption that tutoring is a ubiquitous human practice. Learning is ubiquitous. Perhaps teaching is ubiquitous. Although that depends on how teaching is to be defined. For sure, ethnographers do commonly question the universal distribution of teaching, at least in childhood. It is often claimed that in many cultures, childhood learning will be a rather modest matter of observation, emulation and participation. Examples of children learning through the tutoring practices reviewed in this chapter seem to be particularly scarce (Lancy, 2008; Lancy and Grove, 2010).

Yet tutoring may still be considered a natural human capacity; thereby implying it is one that arises in modern cultures with a certain inevitability. For this to be the case, it does not have to be manifest universally at the present time. It may emerge in cultures according to shifting ecological pressures – being a latent product of deeply rooted human capacities, such as intersubjectivity or the theorising of other minds. One pressure likely to influence its emergence is the gradual penetration of schooling into a society. Rogoff, Mistry et al (1993) described this in their comparative cross-cultural study of adult practices for guiding the young. The presence of schooling may shift the balance between differing traditions: that is, between where adults take responsibility for guidance, as opposed to children doing so through their elective participation in various cultural practices. In the former circumstances, tutoring practices are likely to become a more visible part of domestic child care during the economic growth of a society.

This chapter started with reference to Bloom’s (1984) well-known 2-sigma effect, a calculation that demonstrated the efficacy of tutoring as an act of learning. Yet the intended reach of Bloom’s agenda in that paper was more far-reaching (although it is less often acknowledged). Certainly, he did want to celebrate the potency of tutoring. But he was conscious of the labour-intensive nature of the procedure. He understood it was unrealistic to promote it in school systems unable to furnish the large number of tutors required. So, the bulk of his paper involved gathering effect sizes for other forms of educational intervention, in order to converge on a curriculum ‘package’ that he could reason might be the best possible alternative to unattainable tutoring. Bloom surely remains right in saying that tutoring could not be realistically scaled up to classrooms. The form of dialogue expected for tutoring, as highlighted in this chapter, depends on sustained and small-group intimacy. However, the spirit of tutoring dialogue – talk that invites the learner into self-construction of knowledge – this surely is echoed within modern classroom discourse. Albeit in a stripped-down form, or in a teacher’s modelled dialogues-with-self. A significant social consequence of this is that some students, when they enter schooling, may be better prepared than others for participation in this form of classroom discourse. Memelshtine (2017) has reviewed a number of studies relevant to this: identifying a significant relationship between parental education and contingent scaffolding – which in turn anticipates readiness for and recognition of schooled discourses.

As tutoring becomes more widely manifest within cultural groups, we can ask whether its emergence reflects a trajectory of biological preparedness or one of cumulative cultural transmission. That debate is ongoing (cf. Tomasello, 2009; Brandl, Mace and Heyes, 2023; Leagre, 2017). But it is recognised that the modern ecology of human life has become far too complex for so much understanding to be re-invented afresh by each generation of childhood newcomers. Methods of effective knowledge transmission need to be recruited to deal with the imperatives of fast enculturation – whether they are methods best judged to be grounded in a species history of biological adaptations or a species history of cultural adaptations. The child cast into the fast-changing cultural environment typical of western economies needs early guidance in support of a creative ‘joining-in: that may be a challenge well provided by ready access to tutoring.

9) Psychological themes

As might be expected in a first chapter, theoretical concepts relating to the psychology of learning have come thick and fast. In this final section they will be reviewed in skeletal fashion. Many will re-appear in subsequent chapters.

The social grounding of human learning has been approached by psychology through analyses of the dialogue that takes place during tutoring. One form that dialogue can take in support of learning has been systematised as scaffolding: a specific conversational practice characterised by indirection of guidance, contingency management, and fading of support. Within dialogue structures such as scaffolding, participants exploit the human capacity for intersubjectivity. Ideally, this is recruited in the interests of the learner co-constructing knowledge of the tutoring domain. The learner can exercise that understanding by configuring or re-configuring personal knowledge schemas. Effective outcomes of such construction may depend upon learner’s engaging in processes of self-explaining. The gap between what a learner can construct independently versus their achievement with the guidance of others is known as that individual’s zone of proximal development.

The practice of tutoring is an illustration of distributed cognition. Processes of reasoning and remembering are conversationally distributed between tutoring participants, while their joint thinking can be mediated by the distributed presence of material tools and technologies. In that sense, tutoring illustrates the operation of an externalised mind, while the learning that follows may depend upon an internalisation of these tools and actions into the learner’s mental life. A learning problem’s design, plus the thinking that it requires, and its supportive guidance may all be considered sources of cognitive load. This load arises from the need to manage information flow between the learner’s long-term memory and working memory.

Some of these theoretical concepts have been introduced and positioned here within larger bodies of psychological theory – notably socio-cultural theory and cognitive load theory. The research studies cited in the chapter cannot, taken together, qualify as comprehensive reviews of the research literatures that address themes covered here. But consulting them will illustrate key points of disciplinary practice in the psychology of learning. Thus, they include systematic and meta-analytic reviews of literature. Empirical studies also illustrate the varieties of research method applicable to the topic of tutoring. These include qualitative methods whereby, for instance, dialogue may be scrutinised for meaningful patterns, quantitative methods systematising surveys of human action, and experimental methods that compare innovating learning interventions with control conditions based on business-as-usual.